Making a net-zero emissions building code by 2024 a reality

While operational emissions can be swiftly addressed, there's room for improvement when it comes to embodied emissions

Kevin Lockhart

Efficient Buildings Lead

January 31, 2022

Blogs | Buildings | News

- The federal government has committed to developing a net-zero emissions model building code for provincial/territorial adoption by 2024.

- Energy efficiency remains a cornerstone by which to decarbonize the buildings sector.

- While operational emissions can be swiftly addressed, additional resources are needed to properly assess, and report embodied emissions.

Provinces and territories are now able to preview Canada’s first national net zero energy ready model codes: the “2020 Model Codes“. This is an exciting step towards the decarbonization of the buildings sector. However, it is still only the first step. The 2020 model codes are based on a narrow definition of energy efficiency in new buildings that does not directly consider greenhouse gas emissions.

Recognizing the need to tackle emissions to achieve a net zero buildings sector, the Prime Minister’s recent mandate letter to the Natural Resources Minister included “publishing a net-zero emissions building code… by the end of 2024.”

This article will explore:

-

The definition of net zero emissions buildings and building codes

-

The central role energy efficiency will continue to play in such a code

-

Discuss the need to increase supports for the development of frameworks required for assessing and reporting embodied emissions from buildings

What does net zero emissions mean?

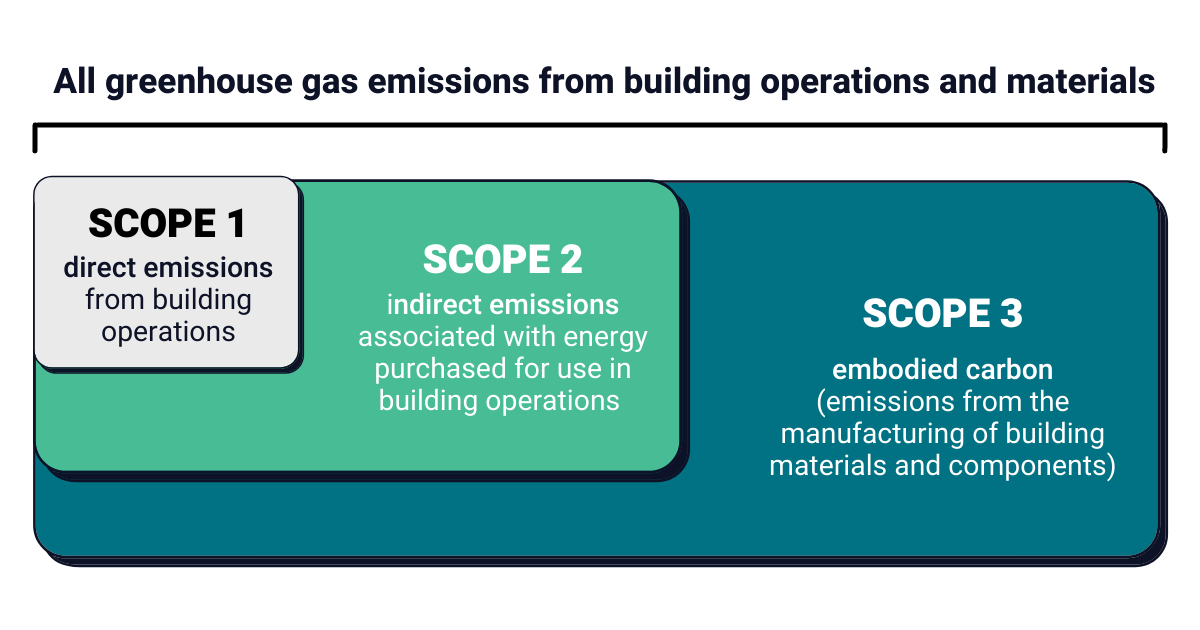

Much like for net zero energy codes, a net zero emissions code can mean both net zero emissions ready or net zero emissions. Both paths cover all greenhouse gas emissions from both building operations and materials. This includes:

-

Scope 1 emissions: the direct emissions that occur from building operations, namely space heating/cooling and water heating.

-

Scope 2 emissions: the indirect emissions associated with energy purchased for use in building operations.

-

Scope 3 emissions: emissions from the manufacturing of building materials and components, commonly referred to as embodied carbon.

Each path recognizes that a net zero emissions/emissions ready building must incorporate passive design features, a robust building envelope, and highly energy efficient equipment and appliances. These measures help to greatly reduce the building’s energy demand and, in turn, allow for the use of appropriately sized renewable energy systems for building operations, or lessen the building’s energy demands on the existing energy supply. Embodied carbon associated with the full lifecycle of structural and envelope is also accounted for.

Once the energy supply is fully decarbonized, a building constructed to net zero emissions ready building code requirements will reach net zero emissions without any further changes to the building or its equipment.

Going a step further, a building constructed to net zero emissions building code requirements produces or procures enough carbon free energy to immediately meet all of the building’s operational energy needs.

Energy efficiency continues to be the cornerstone of a net zero emissions building code

The benefits of energy efficient buildings ranging from greater occupant comfort and favourable health and safety outcomes for occupants to those that contribute to climate resiliency and adaptation are well documented. Nonetheless, there is a danger that lower carbon building materials are treated as an “offset” to energy efficient designs and construction practices, such as enhanced airtightness performance. However, energy efficiency measures are crucial to reducing both operational and embodied carbon emissions in new buildings.

Reducing both operational and embodied emissions in the building sector begins with cutting energy wasted throughout the building’s lifecycle. At the design stage, buildings intended to be highly energy efficient typically reject needlessly complex roof or floor plans in favour of simpler building ‘form factors’ that reduce the building envelope area. As a result, less materials are needed and there are fewer areas that require detailed attention to ensure building control layers are complete. These measures also help minimize construction waste, and wasted resources, throughout the extraction, transportation, and application of materials and, as such, contribute to further reductions in embodied carbon.

In operation, these same energy efficiency measures are a critical component in building decarbonization as they reduce a building’s energy needs to the degree that renewable energy or zero carbon energy sources can meet all space conditioning requirements. Reducing the building’s operational energy demand supports the use of highly energy efficient and right-sized heating systems, such as air source heat pumps. As a result, energy resources are freed for higher value uses, like meeting growing demands for widespread electrification (of both buildings and vehicles) without the need for additional electricity system infrastructure.

In sum, achieving significant emission reductions begins with minimizing the building’s energy demands, ensuring mechanical systems use zero-carbon fuels, and using low-carbon construction materials and building components. These fundamental steps are key as there is a risk that some actors might seek to avoid energy efficient design changes and construction practices assuming that simply switching existing materials for low-carbon building materials will achieve the same outcomes. That will create missed opportunities to achieve deep emissions reductions while capturing the many co-benefits of energy efficiency.

Platforms to cut emissions from building operations are already in place

Given that the emphasis on both operational and embodied emissions from buildings has only come to the fore in the last decade, there are few examples of net zero emissions building codes in place in other jurisdictions.

In Canada, we can point to voluntary initiatives such as the Canadian Green Building Council’s Zero Carbon Standard, and provincial efforts underway such as the British Columbia’s plan to add a new carbon pollution standard to the BC Building Code.

Beyond our borders, the International Codes Council’s (ICC) Zero Code offers an illustrative example of how to eliminate operational emissions by leveraging existing energy efficiency standards to support the construction of net zero emissions buildings. Building on the energy efficiency requirements of existing standards such as ASHRAE Standard 90.1-2019 / IECC 2021, the Zero Code offers a flexible framework with additional requirements aimed at decarbonizing building operations.

Similarly, using existing compliance paths within the National Energy Code for Buildings (NECB) and National Building Code (NBC) as a platform, a Canadian net zero emissions ready code could require the use of 100% efficient space and water heating equipment and appliances, immediately or in a tiered approach, to ensure no emissions are generated from building operations. In effect, a net zero emissions ready code will enable new buildings to achieve net zero operating emissions with the addition of renewable and carbon-neutral sources located either on- or off-site, or when energy sources are decarbonized.

Tackling scope 3 emissions, on the other hand, is a more complex task as it requires eliminating the embodied carbon within construction materials.

Additional supports needed to measure, and report embodied carbon accurately

A net zero emissions code addresses all three levels of emissions, this includes emissions embedded within structural and building envelope materials. These embodied emissions are created because manufacturing processes and other upstream production systems can be energy inefficient and resource intensive or use production inputs with high climate impact.

Efforts to assess the embodied carbon of construction materials have thus far been impeded by a relative lack of adequate data on the carbon content of materials and under-developed systems for tracking and transparently reporting information across supply chains. The many variations in current standards for reporting, which can include possible exemptions or variations in how product lifecycles are estimated have made a standardized template for assessing and reporting the embodied carbon of materials an ongoing challenge.

Two notable efforts to build the knowledge infrastructure required to track and report embodied carbon are underway. Developed by Builder’s for Climate Action and Natural Resources Canada, the Carbon Use Intensity metric offers a building level approach that focuses on the embodied carbon impact of a building as a whole. It considers not only the choice of materials according to their carbon impact, but also the efficiency, ability to re-use, lifespan, and potential circularity of the material.

Alternatively, the National Research Council’s low-carbon assets through life cycle assessment (LCA2) initiative takes a product level approach that will offer builders and designers a means to identify materials with the lowest carbon footprint.

Each aim to address shortcomings in existing approaches to Life Cycle Analysis and Environmental Product Declaration, establish guidelines that account for variation in the construction, use, and end-of-life stages of product, and provide a framework for ongoing updates to that reflect upstream changes to manufacturing processes and materials. Those updates are critical because the end-goal should be for the net-zero emissions code to re-shape building sector demand to such an extent that it induces upstream production changes.

To truly achieve net zero emissions in the Canadian buildings sector we need to accurately measure the embodied carbon within building materials and components. Initiatives like those above that seek to assess and reduce embodied emissions are urgently needed and warrant increased government support to contribute to the effectiveness of a Canadian net zero emissions building code.

Net zero emission building codes are the next step

Canada’s national model codes represent one of the most effective policy instruments by which to accelerate our transition to zero-carbon buildings. No instrument in the government’s current climate toolbox is as effective in transforming the market for net zero energy and emissions buildings as building codes can be.

Since their introduction to the Canadian market in the 1940s, building codes have helped raise the minimum performance of Canadian buildings in terms of safety, health, and energy. Applying this same approach to the carbon performance of buildings is an important step in the market transformation of the buildings sector by sending clear market signals to manufacturers who, in turn, can invest in the long-term low-carbon technologies, processes, and infrastructure to meet the demands of the buildings sector.

The tiered framework within the 2020 model codes is an opportunity for provinces and territories to shift to increasingly energy efficient construction processes and practices, a necessary complement to achieving net zero emissions.

With the addition of a net zero emissions ready/emissions code by 2024, we can quickly develop a policy structure to address operational emissions. Then, with increased support for government initiatives already underway, Canada can demonstrate leadership in standardized methodologies for assessing and reporting embodied emissions.

Building codes play a key role in emissions reductions. They have the ability to reduce emissions quickly — but they often move slowly, limiting the potential impact. Municipalities can help change this.