Unlocking the potential of Mandatory Building Performance Standards through benchmarking

Sharane Simon

Research Associate, Efficiency Canada

June 16, 2023

Blogs | Buildings | MBPS | News | Provincial Policy

- Benchmarking data provides essential information on a building’s baseline energy use. It helps set performance goals and tracks the impact of energy efficiency investments.

- Disclosure of benchmarking data fosters transparency, enabling policymakers to monitor building performance and incentivize energy efficiency.

- Overcoming implementation challenges and improving data transparency are vital for achieving energy efficiency goals.

- Lessons from international experiences can guide the development of effective benchmarking policies in Canada.

Mandatory Building Performance Standards (MBPS) are an essential policy tool for achieving energy, emissions, and water reduction goals in our worst performing buildings. They set performance targets that increase over time, a necessary complement to the Alteration to Existing Building code (AEB), which is triggered by the voluntary actions of the building owner.

Benchmarking data plays a crucial role in understanding building performance. Without it, we can’t design effective MBPS programs. The framework for benchmarking has been available in Canada for a decade, but challenges in implementation and data privacy hinder mass adoption. Below, we explore solutions to enhance benchmarking adoption, drawing on lessons from other jurisdictions.

You can only manage what you measure

Benchmarking data provides essential information on a building’s baseline energy use. It measures a building’s performance over time and compares it to similar building types and sizes. It can be used to set performance goals and track the impact of energy efficiency investments. While this information gathering component contributes to the building owner’s understanding and decision-making, the full impact of benchmarking is only realized when the data is made publicly available.

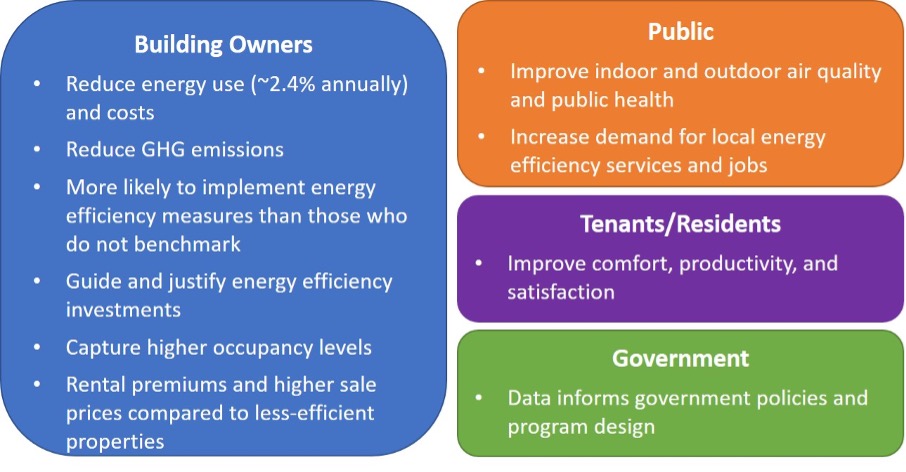

Disclosure, also known as transparency, makes benchmarking data visible to the marketplace, typically using a labelling system. This enables policymakers to monitor how their jurisdiction’s building stocks are performing and responding to new policies, and improves the literacy of the public. The public, utilities, industry, and government are all well-positioned to capture the many benefits of benchmarking and disclosure (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Benefits of benchmarking and transparency. Adapted from IMT (2015) and EPA (2021)

Benchmarking and disclosure framework in Canada

In Canada, benchmarking and transparency policies are administered at the provincial and municipal levels, with support from the federal government. The feds provide technical information and training resources, and manage ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager — the primary benchmarking tool in Canada. They also fund innovative projects and tools like GRID, an online platform that helps jurisdictions manage and administer their benchmarking programs and produce insights at a program level. ENERGY STAR uses a 1-100 score. A score of 50 indicates median energy performance while a score of 75 or more indicates top performance.

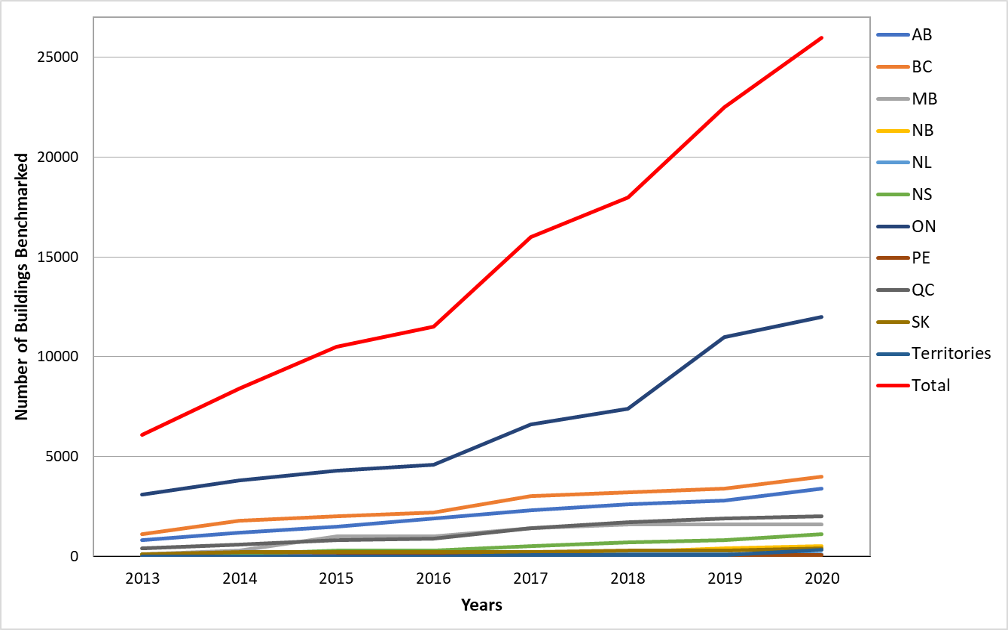

As of 2020, 26,000 Canadian buildings covering 318.5 million square metres have used ENERGY STAR to measure and track energy use. It is equivalent to 5 per cent of all commercial buildings or 45 per cent of their floor area (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Overall benchmarking growth in Canada. Source: NRCAN (n.d.)

Forty-five per cent of benchmarked buildings are within Ontario, mostly due to Energy and Water Reporting and Benchmarking (EWRB), Canada’s first and only mandatory provincial benchmarking program (Fig. 2; Table 1). Since 2021, Vancouver and Montreal, have adopted energy and carbon reporting for large commercial and multifamily buildings. The number of benchmarked buildings outside of Ontario has increased slowly, despite efforts to implement voluntary commercial and institutional benchmarking programs, and mandatory reporting of government-owned buildings (Table 1).

Table 1 Summary of Canada’s leading benchmarking programs

| Jurisdiction or program name (implementation date) | Program type | Building type and size | Type of disclosure | Additional details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec (2007) | Mandatory | Government-owned buildings including schools and health and social services | Online report and tables | The Government of Québec set emissions reduction targets for select buildings; benchmarking is prioritized to measure and track progress. Aggregate data of specific building types are provided and displayed in tables and graphs. |

| Ontario (2017) | Mandatory | Commercial, industrial, and multi-unit residential buildings; ≥ 4645 square metres | Open data website | Annual reporting from buildings greater than 23,226 square metres in 2017 was lowered to 9,290 square metres in 2019 and 4,645 square metres in 2023. A subset of the benchmarking data is anonymized, stripped of location details, and publicly disclosed. |

| New Brunswick (2021) | Mandatory | Government-owned facilities including healthcare, schools, and community colleges | Online annual report | Limited public disclosure as the current performance of the covered buildings are not published. |

| Montreal (2021) | Mandatory | Commercial, institutional, and multi-unit residential buildings; ≥ 2,000 square metres | Annual report | Reporting from buildings ≥ 15,000 square metres in 2022 will be lowered to 5,000 square metres or ≥ 50 dwellings in 2023 and 2,000 square metres or ≥ 25 dwellings in 2024. Published data will initially not identify any building’s performance. However, once the rating system is in effect, the building’s address and rating will be available on the City's website. Failure to comply will result in a fine. |

| Vancouver (2022) | Mandatory | Commercial and multi-family buildings; ≥ 4,645 square metres | TBD | Reporting from commercial buildings ≥ 9,290 square metres in 2024 will be lowered to 4,645 square metres in 2025 and include multi-family buildings ≥ 9,290 square metres; by 2026, both commercial and multi-family buildings ≥ 4,645 square metres will be required to report. Resources will be provided to help owners comply with reporting requirements. |

| Edmonton (2017) | Voluntary | Commercial and institutional buildings; > 93 square metres | Report and online map | Annual consent must be provided to disclose data. On average, there is a 80 per cent retention in program participation. Edmonton Building Energy Retrofit Accelerator program requires participation in the benchmarking program to be eligible for financial incentives to offset retrofit costs. |

| Défi-Énergie en immobilier (2018) | Voluntary | Commercial, institutional and multi-unit residential buildings; any size | Online report | Défi-Ènergie includes four performance awards for building owners and consulting firms. |

| Benchmark BC (2019) | Voluntary | Commercial and institutional buildings; any size | Online map | Benchmark BC includes 22 municipal partners, mostly covering office and multi-family buildings. Building owners can opt out of disclosing data online. |

| Winnipeg (2019) | Voluntary | Commercial and institutional buildings; ≥ 1858 square metres* | Open data portal; online map | Building owners can disclose all available data and metrics in their portfolio or opt to provide a read-only access of historical energy data. |

| Ottawa (2019) | Voluntary | Commercial and institutional buildings; > 1858 square metres | Online map | Building owners can receive discounted building envelope thermal inspections, access to training programs and be eligible for future retrofit financing programs. |

| CaGBC Disclosure Challenge (2019) | Voluntary | Commercial, institutional and multi-unit residential buildings; any size | Online map | The website contains case studies, including the building’s past and future activities and strategies to increase energy efficiency and reduce emissions. |

| Calgary (2021) | Voluntary | Commercial and institutional buildings; any size | Online map | Building owners can fully disclose building data, not publicly disclose data but incorporate in program statistics (aggregate disclosure), or use hybrid disclosure where owners can select some buildings for full or aggregate disclosure. |

| Nova Scotia (2021) | Voluntary | Commercial, institutional and multi-unit residential buildings; TBD | Online map | Building owners must consent to display data on Efficiency Nova Scotia’s website, as well as building-specific disclosure. |

*Smaller sizes are considered for Public Sector Organizations (PSO) or other interested building types

Considerable progress has been made. But efforts to drive mass uptake and unlock the full potential of benchmarking have been hampered.

Most of the building performance data publicly disclosed come from voluntary programs. However, a perception remains that disclosure may create an unfair business environment for poorly performing buildings due to their heritage status or lack of investment capital for necessary upgrades. Some stakeholders prefer data to be presented in aggregate or anonymized formats similar to the EWRB program, where the data is used for policy development by the jurisdiction. Unfortunately, these rationales do not reward commercial building owners investing heavily in energy and GHG conservation measures to remain competitive. Nor do they encourage building owners to partake in the range of financing and funding options available from the government, utilities, and financial institutions. Additionally, heritage building owners can be exempted from disclosure as they are subject to different standards and guidelines.

Implementation challenges are complex and have also acted as a barrier to progress. These include the actual or perceived limits of a municipality’s authoritative powers, difficulties in benchmarking multi-tenant buildings, campus-style energy distribution where one energy meter feeds multiple buildings, and a lack of direct data connections between the utility providers and data management systems. These policy and technical challenges can be resolved by allocating adequate resources and significant collaborative effort.

The following sections explore how other jurisdictions have approached benchmarking to drive interest and market uptake over time.

Case study: evolution of benchmarking and transparency policies in Europe

In 2002, the Energy Performance of Building Directive (EPBD) directed European Member States to implement energy performance measures. It included minimum energy performance standards and mandatory energy performance certificates (EPC) for new and some existing buildings (Table 2). EPCs are Europe’s primary benchmarking and labelling scheme. They use a rating scale from A+ (most efficient) to G (least efficient). It was a novel directive, and Member States were slow to act on these policies. This resulted in the recasting of the EPBD in 2010, 2018, and 2023, which prioritized improving the transparency and quality of the EPC.

Table 2 The evolution of the energy performance certificate during the EPBD recasts

| Date | EPC-specific directives introduced or reinforced during EPBD recasts |

|---|---|

| 2002 | ➔ EPCs with a 10-year validity for all buildings, apartments, and units that are newly constructed, undergoing major renovation, being sold or rented (art. 7). ➔ EPCs to include current legal standards, benchmarks, and cost-effective recommendations for the improvement of the building’s energy performance (art. 7). ➔ Display EPCs in a prominent position in buildings > 1,000 square metres that are occupied by authorities and institutions that provide public services (art. 7). |

| 2010 | ➔ Reduction of floor area to 500 square metres from 2013 and 250 square metres from 2015 (art. 12). ➔ Increase the visibility of the energy label in advertisements (art. 12-13). ➔ Assure the competence of the certifiers in the accreditation procedure and the provision of an updated list of accredited companies (art. 17). ➔ Introduce an independent control system to randomly check a statistically significant percentage of all EPCs issued annually to verify the input data and the results (art. 18). ➔ Penalties for non-compliance, including not issuing an EPC, handing it over during sale or rental, and displaying in commercial advertisements (art. 27). |

| 2018 | ➔ Discretion to require the issuance of a new EPC when a building system is installed, replaced or upgraded and the energy performance is impacted (art. 8). ➔ National database for EPCs, for at least public buildings (art. 8). |

| 2023 | ➔ Extend EPC issuance to buildings with a refinanced mortgage (art. 17). ➔ Standardization of EPC to include numeric indicators for primary and final energy use, life-cycle GHG emissions, total annual energy consumption and cost effective recommendations for improvement of energy performance (art. 16). ➔ Harmonize EPCs between Member States by specifying an energy scale from A to G where A corresponds to zero emission building and G represents the 15 per cent worst-performing buildings in the national building stock by 2026 (art. 16). ➔ Simplify process of updating an EPC to make it affordable/no cost (art. 16). ➔ Compile EPC registers (art. 16 and 17) and set-up open-access national databases with aggregated and anonymised building stock data (art. 19). ➔ The EPC for D to G classes is reduced from 10 years to five. This is to ensure that they contain up-to-date information (art. 16). |

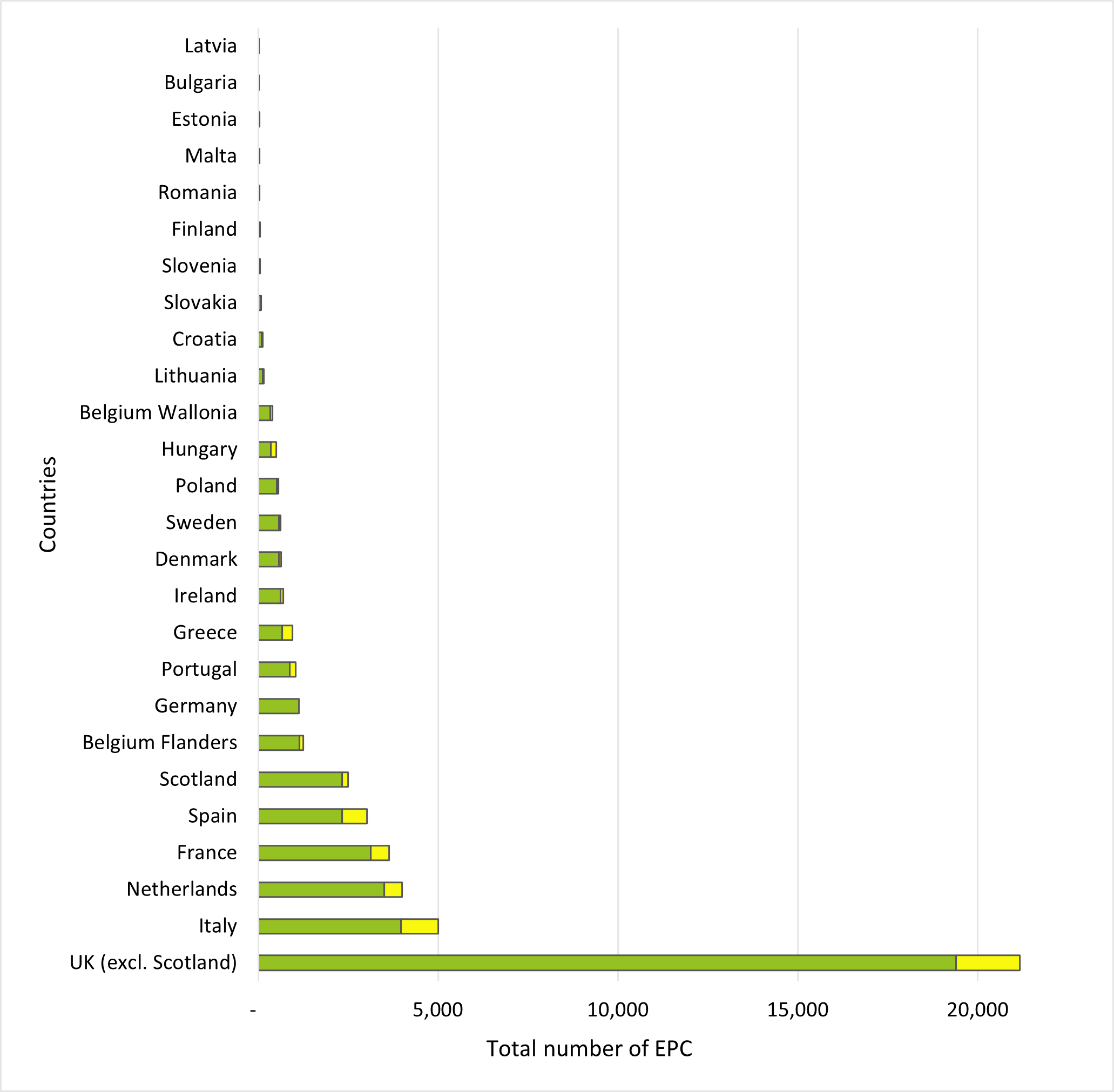

Today, EPCs are used in all Member States. More than 45 million residential EPCs have been issued, with almost six million furnished each year. Still, less than 10 per cent of existing buildings in several Member States have been certified (Fig. 3). This is attributed to the size of the Member State, complex building ownership structure, number of real estate transactions, and quality and fair pricing concerns. With each recast, the European Commission strengthened the EPC framework through preemptive and reactive measures (Table 2). Member States are also required to simplify the process of updating an EPC, and to make it more cost-effective.

Figure 3 Number of EPCs registered per country/region. The yellow part of the bars indicates the share that was issued per year during the most recent years (2016-2019). Source: X-tendo (2020)

To ensure transparency, EPCs must be prominently displayed in a non-residential public building. When buildings are advertised for sale or rent, the energy performance indicator (A+ to G rating) of the EPC must also be published. Eleven of 27 Member States have central or regional EPC registries used for quality control monitoring of the certification process. The most recent recast requires Member States to set up national public databases with aggregate, anonymized building stock data. Access to building-specific EPCs will be limited to authorized individuals such as building owners, tenants, certified experts, prospective tenants and buyers, and financial institutions assigned to their non-trading book. The data will feed into the EU Building Stock Observatory, which will monitor the progress of Member States as they implement directives at a national and regional level.

Case study: subnational growth of benchmarking in the U.S.

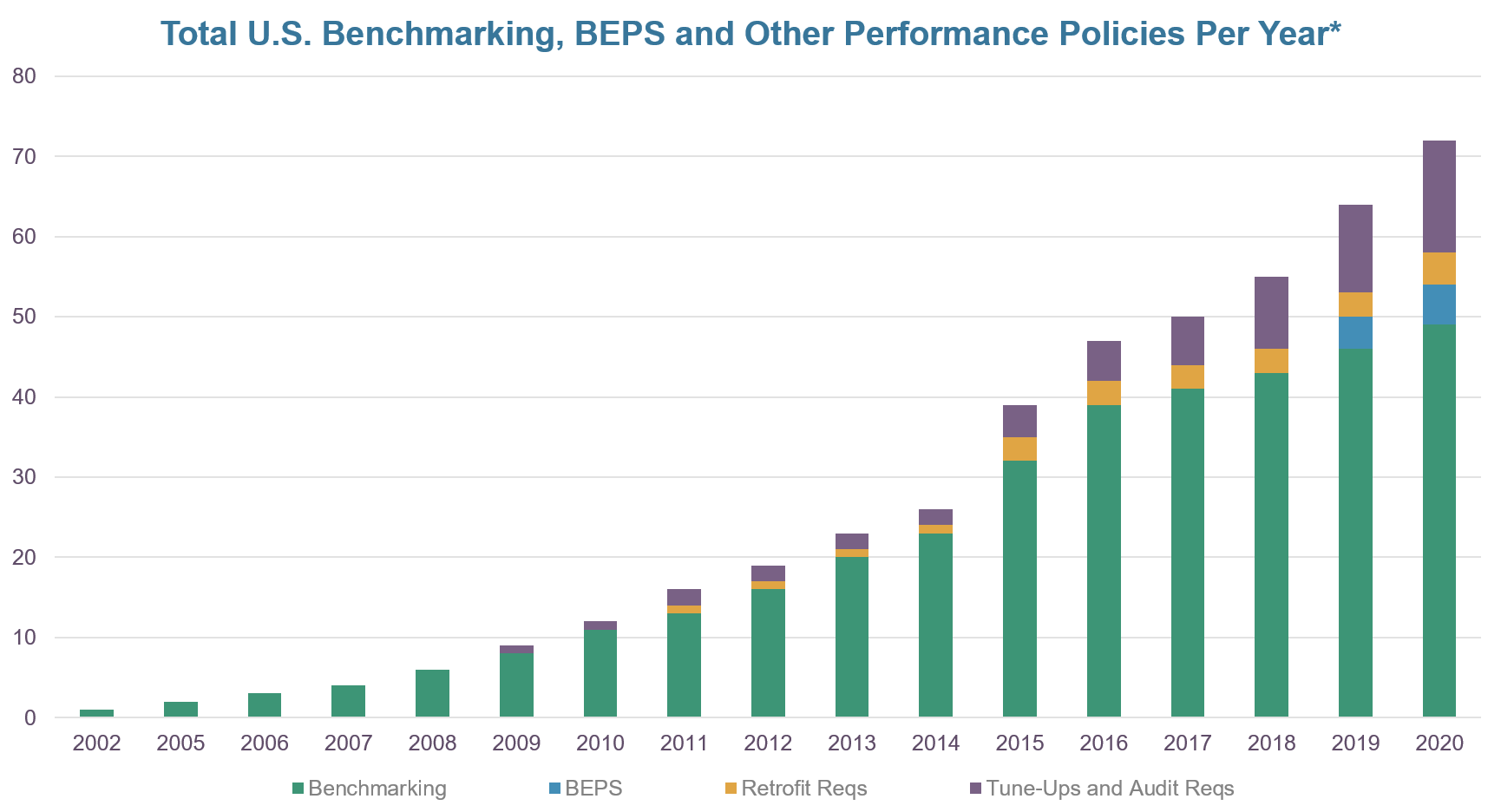

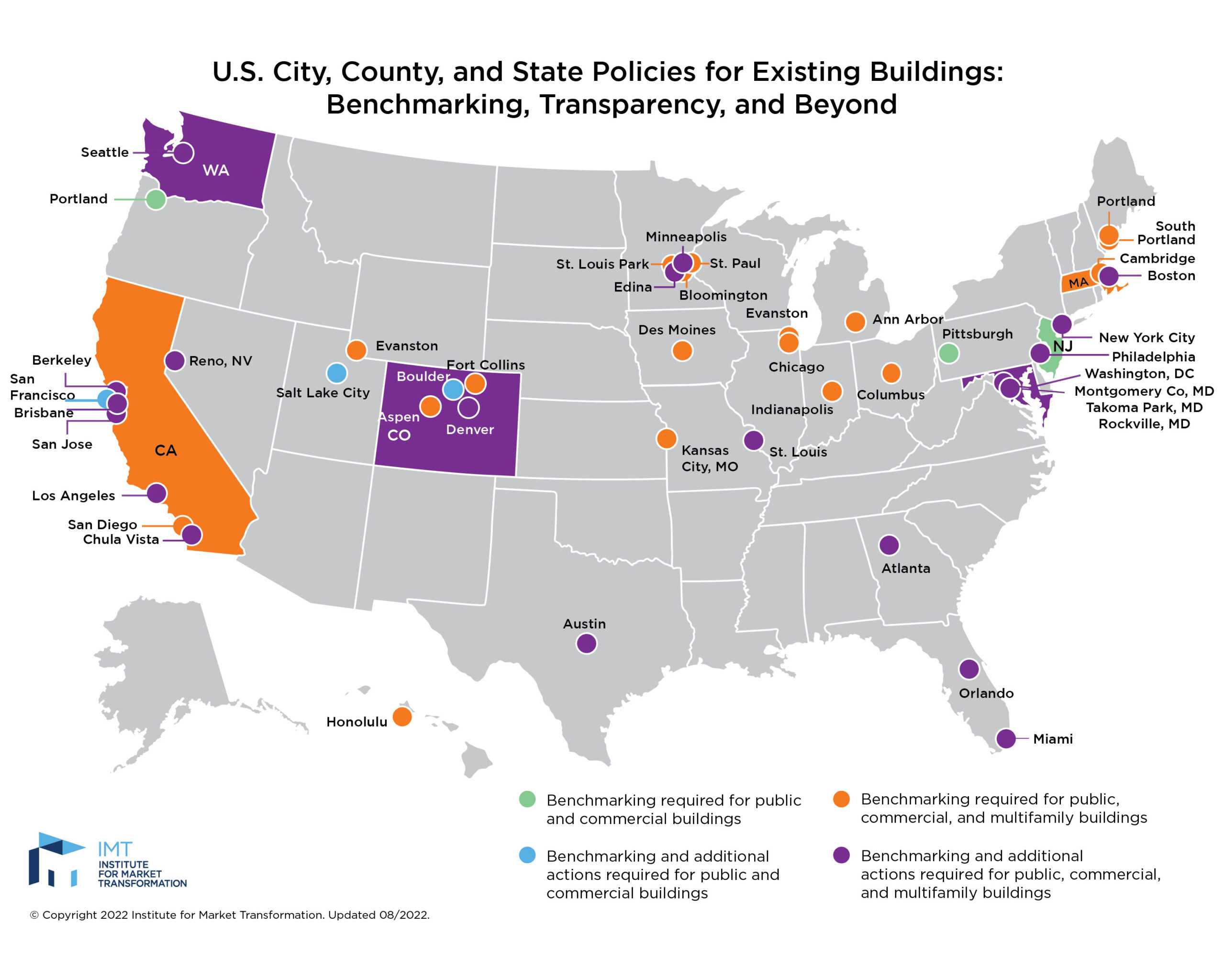

In the U.S., states and cities are responsible for implementing benchmarking and transparency policies. Since the early 2000s, more than 40 state and local jurisdictions have required reporting and disclosure of energy consumption data from commercial, multi-family, and publicly-owned buildings (Fig. 4). Most jurisdictions require the use of EPA’s ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager for measurement and tracking.

Figure 4 Uptake in benchmarking, Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS), and other policies since 2002. Source Calico Energy.

There is no cost to apply for certification and jurisdictions tend to provide free or low-cost technical assistance online or through one-stop-shops. However, some ordinances may require verification by a qualified professional at a cost (up to hundreds of dollars), depending on the complexity of the building, the state of benchmarking data, and the number of buildings within the portfolio. EPA assists building owners such as school districts, religious and non-profit organizations who lack financial resources to find licensed professionals who can provide cost-free verification services.

To overcome challenges related to multi-family building and whole building benchmarking, utility companies provide a data access solution. This allows aggregate whole-building data to be provided to building owners when the aggregation threshold is exceeded–typically between three to five tenants/accounts. This approach preserves customer data privacy as building owners will not be able to identify the specific energy consumption of their tenants. Below this threshold, the building owner must obtain consent from each tenant before the utility can release aggregated consumption data. The Green Button has also emerged as a leading solution where utilities provide energy data to approved end-users in a standardized data format.

Mandatory benchmarking programs typically disclose building performance data via government websites, annual reports, downloadable Excel spreadsheets, and interactive online maps. Some jurisdictions, such as New York City and Chicago, also require displaying an energy efficiency rating label or placard on a prominent location in the building. Jurisdictions use a range of administrative mechanisms, including fines and non-financial penalties like written warnings to enforce benchmarking policies. Some benchmarking programs have complementary policies such as voluntary campaigns, building energy audits, retro-commissioning, or building performance standards (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 U.S. jurisdictions with mandatory building energy benchmarking and transparency policies for existing buildings. Source: Institute of Market Transformation (2022).

Case study: Voluntary reporting and mandatory benchmarking in Australia

In Australia, the National Australian Built Environment Rating System (NABERS) is a voluntary tool for commercial buildings that produces an energy rating from one to six stars in half star increments. Buildings are benchmarked and rated based on the base building, tenancy, or the whole building energy usage. Over time, the NABERS tool has expanded to include shopping centres, data centres, public hospitals, apartment buildings, retirement living and residential aged care, warehouses, and cold stores. It can also be used to benchmark water consumption for most of these building types.

To increase the uptake of the voluntary NABERS rating, the Australian Government established the Commercial Building Disclosure (CBD) program. It requires any office building > 1,000 square metres of floor space to obtain, register, and disclose a Building Energy Efficiency Certificate (BEEC) before the building is sold or leased. A BEEC lasts up to 12 months and includes a NABERS base building rating, a tenancy lighting efficiency assessment, and general energy efficiency recommendations. By using the base building rating that excludes the tenant energy usage, building owners are not impeded by data access issues, which has potentially contributed to NABERS’ market uptake. Beyond disclosing to potential buyers or lessees, the BEECs must also be publicly accessible on the Building Energy Efficiency Register and via promotional materials. Owners can be exempted from disclosing benchmarking data if the building area is used for security operations, has unique characteristics that make it non-assessable, or has less than 75 per cent office space.

NABERS now represents over 22 million square metres of office space

Everyone has a role to play

Canada has made considerable progress in building benchmarking. However, there is still room for improvement in our approach to policy design, transparency, data access, multi-tenant implementation, and jurisdictional authority. Lessons from international experiences can guide the development of effective benchmarking policies in Canada.

The federal government should consider making reporting and benchmarking for eligible buildings mandatory. Provincial governments should be more proactive and agile in mandating benchmarking or enabling municipal powers, while prudently leveraging federal support. Municipalities should continue to take action to find creative solutions to their challenges, including finding ways to foster regional collaboration to reduce administrative burdens. And, utility companies should seek ways to enable this policy by offering whole building aggregate data and data access solutions such as Green Button.

Coordinated collective action, alongside an iterative culture of experimentation, can help Canada capture the benefits of leading benchmarking policies. In turn, this will set the stage for evidence-based mandatory building policies that will help cut energy waste and emissions in our existing buildings.