Canada drops from 10th to 13th in international ranking on energy efficiency

Scores higher on national policy, yet near bottom on performance

Brendan Haley

Sr. Director of Policy Strategy

April 6, 2022

Blogs | Federal Policy | News

- The International Scorecard benchmarks countries on policy and performance.

- Canada ranked 7th in energy efficiency policy , but 23rd in performance.

- Given the amount of energy waste, Canada needs world leading policies to improve performance.

Today (April 6, 2022) the latest International Energy Efficiency Scorecard is out. Produced by our colleagues at the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy, it assesses the policies and performance of the world’s top 25 energy consuming countries.

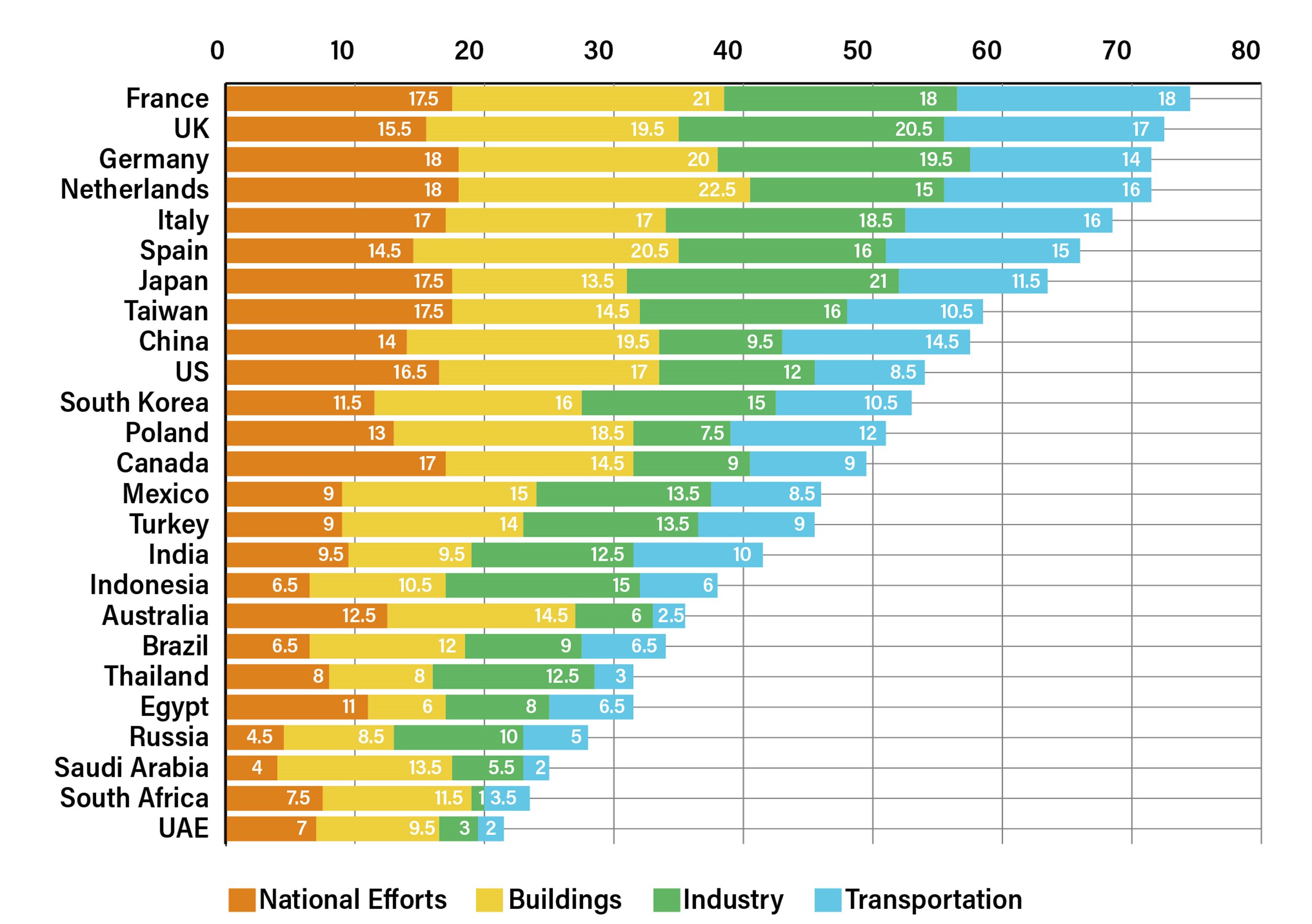

Canada is ranked 13th overall (between Poland and Mexico), with 49.5 points out of 100. France is in first place, and the United States is in 10th. This is a drop in rank from Canada’s 10th place position in the 2016 and 2018 Scorecards.

Below, we dig into the results, and discuss what we can learn to improve energy efficiency in Canada.

Better policies than performance

Similar to the Efficiency Canada Provincial Policy Scorecard, the International version compares countries on both policy and performance.

Policy metrics include areas like spending on energy efficiency programs and R&D; appliance and equipment standards; industrial energy management policy; and transportation fuel economy standards.

Performance metrics include economywide changes in energy intensity; electric vehicle sales; use of public transit; and energy intensity of residential and commercial buildings.

Canada does significantly better in policy than it does in performance.

If ranked solely on policy metrics, Canada would be in 7th place, just ahead of the United States and behind the Netherlands. Compared to other countries, Canada spends the most on energy efficiency R&D, it has the third highest number of minimum performance standards for appliances and an aggressive GHG reduction target.

When it comes to performance, Canada ranks 23rd. Even after normalising for factors such as climate and industrial structure, Canada has a very energy intensive economy. For example, Canadian residents use the second highest amount of energy per capita; commercial buildings have the 3rd highest energy use per square metre; and Canadians and Americans travel the most kilometres per year in private vehicles.

What explains the difference between policy and performance? Of course there are structural factors influencing Canada’s energy efficiency performance, such as larger geography, natural resource sectors, and larger houses. But there is no shortage of energy waste. High energy intensity usually indicates lots of energy saving potential. As a wealthy country, Canada can make changes that enhance productivity, prepare us for weather extremes, and reduce inequality.

Performance is a lagging indicator and policy is aimed at shaping future outcomes, so we have yet to see the influence of policies introduced in the last few years. Yet, the performance metrics shows Canada has a long way to go. In future Scorecards, Canada should be leading the policy rankings by adopting all of the international best practices available and then pioneering new policy innovations.

The Scorecard is divided into national efforts, buildings, industry, and transportation. Below are some highlights from each section.

Source: Overall scores and rankings, 2022 International Energy Efficiency Scorecard, ACEEE

National efforts

Canada scored well above average in this category, ranking 6th overall. This higher score takes into account Canada’s commitment to reduce GHGs 40-45% below 2005 levels by 2030; incentive programs available in commercial, residential, and industrial sectors; the highest per capita spending on R&D; and good data availability. The relatively slow pace of improving economy-wide energy efficiency brings down Canada’s scores in this category.

Canada ranked first in per capita energy efficiency spending. This is a metric where the Scorecard notes significant data availability issues in other countries, so Canada’s rank might be influenced by data availability and how spending was estimated. Few countries had annual utility spending figures, and Canada’s data came from Efficiency Canada’s Provincial Scorecard. The International Scorecard estimated annual government spending for Canada using annual average committed budgets, which have significantly increased with recent policy changes such as the Canada Infrastructure Bank Commercial Buildings Retrofit Initiative, and the Greener Homes program. However many of these funds are not spent yet.

The size of the Energy Services Company (ESCO) market is one area where Canada could improve. ESCO’s provide energy efficiency improvements as a service, usually taking on performance and financing risks. It provides an indicator of effective business models and creative financing. China is in the lead with an ESCO market making up 0.13% of GDP, while Canada’s market is 0.02%. The above-mentioned Canada Infrastructure Bank as well as the Greening Government Strategy are new policies that encourage ESCO business models.

Buildings

Canada achieves a median score in buildings, ranking 13th. Netherlands is in first.

Canada gets high scores here for appliance and equipment standards. Alongside the United States, Canada regulates a high number of appliances and has mandatory energy performance labels.

As noted above, Canada’s buildings are very energy intensive, even after using heating degree days to control for climate. The Scorecard measures energy intensity per floor area, as well as per capita and per unit of GDP. Canada, the United States, and Australia do particularly poorly on per capita indicators because the average house is double the size of dwellings in other countries.

Mandatory ratings and performance standards is an area where Canada can catch up. Most European countries have national codes or performance standards that apply to existing buildings, led by the EU Buildings Performance Directive. In Canada, we see municipalities like Vancouver and Montreal taking the lead on requiring energy and GHG performance from existing buildings. Nationally a “retrofit code” is scheduled to be developed by 2024, yet it is unclear if it will be triggered solely by voluntary renovations or if it will also seek to bring all buildings up to net-zero performance levels.

For new buildings, Canada recently published a building code that establishes a pathway to get to net-zero energy-ready buildings, perhaps as early as 2025. The Netherlands is already requiring commercial buildings to be “almost energy neutral”.

The authors note that future International Scorecards will consider low-income energy efficiency policies. Canada has yet to develop a strategy or make retrofits accessible to low-income Canadians. This is an area where there is much to learn from other jurisdictions.

Industry

The industrial category is the only one where Canada is below the median scores Canada ranks 19th in this category. Japan is the top country, followed by the UK and Germany. Canada uses a significant amount of energy to produce a dollar of GDP compared to other countries.

Canada receives points for Natural Resources Canada Industrial Energy Management program, however the estimate of the number of ISO 50001 certifications is low compared to other countries. The recent Canadian Emissions Reduction Plan included a funding boost to expand ISO 50001 certification and energy management systems, especially for small and medium sized industries.

Other countries like Japan, Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom have national laws or regulations requiring periodic energy audits and/or requirements that large industries have an on-site energy management expert. Canada does not have any of these mandatory policies, and few provinces actively encourage energy management system certification as noted in our provincial policy scorecards.

Transportation

Canada receives a median score for transportation, ranking 13th. France is first and the United States ranks 16th.

Canada and the United States have the lowest fuel economy performance for passenger vehicles. Fuel economy in Canada is listed as 8.9 litres per 100 km, compared to 5.2 in Italy.

4.2% of new car sales were electric vehicles in Canada in 2020 compared to 25% in The Netherlands (global leaders like Norway were not among the countries scored). Canada’s Emissions Reduction Plan aims to change this picture by requiring 100% of light-duty vehicles sales to be zero-emission by 2035, and all medium-to-heavy duty sales to be zero emission by 2040.

One area where Canada leads is in fuel efficiency standards for tractor trucks, where a 35% improvement below baseline is required.

The Scorecard also includes indicators demonstrating the need to move people and goods without the use of cars or trucks. Canada invested 12 cents in rail transit for every dollar it invested in roads in 2017. The United Kingdom and France both invested more in rail than roads. Canada and the United States are also at the bottom in the passenger kilometres travelled by public transit among countries where data was available.

Conclusion

The International Scorecard should remind us just how many opportunities there are to improve energy efficiency in Canada given the energy intensity of the economy.

The policies fare better than performance. Given how much Canada has to improve, we cannot settle for average or ineffective policies. Canadian policies need to be world leading.

There is an opportunity to catch up to European countries by encouraging the use of more mandatory policies for new and existing buildings, appliances, industry, and transportation systems. Yet to significantly change the energy efficiency of our economy, Canadians need to pioneer how to make deep savings in energy and emissions faster than anywhere else. The retrofit of our existing building stock in particular should be prioritised as a national mission.

Finally, many thanks to the ACEEE team who put together this latest Scorecard. Collecting these data from several different countries is not an easy task, and is useful for those working in their respective national policy environments.